Press / Media

TGC in the Media

The Hill Times:

Immigrant women trained in STEM are an invisible talent pool

Instead of making full use of this much-needed supply of talent, we do not recognize or remove the many obstacles in their way.

OPINION | BY THAO PHAM | January 24, 2024

We have all likely encountered an immigrant working a job that was far below their expertise and education.

Canada underutilizes the talents and potential of its immigrant population. Many are under-employed and underpaid. Immigrant women trained in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) comprise perhaps the richest talent pool that our country needs to tap into more successfully.

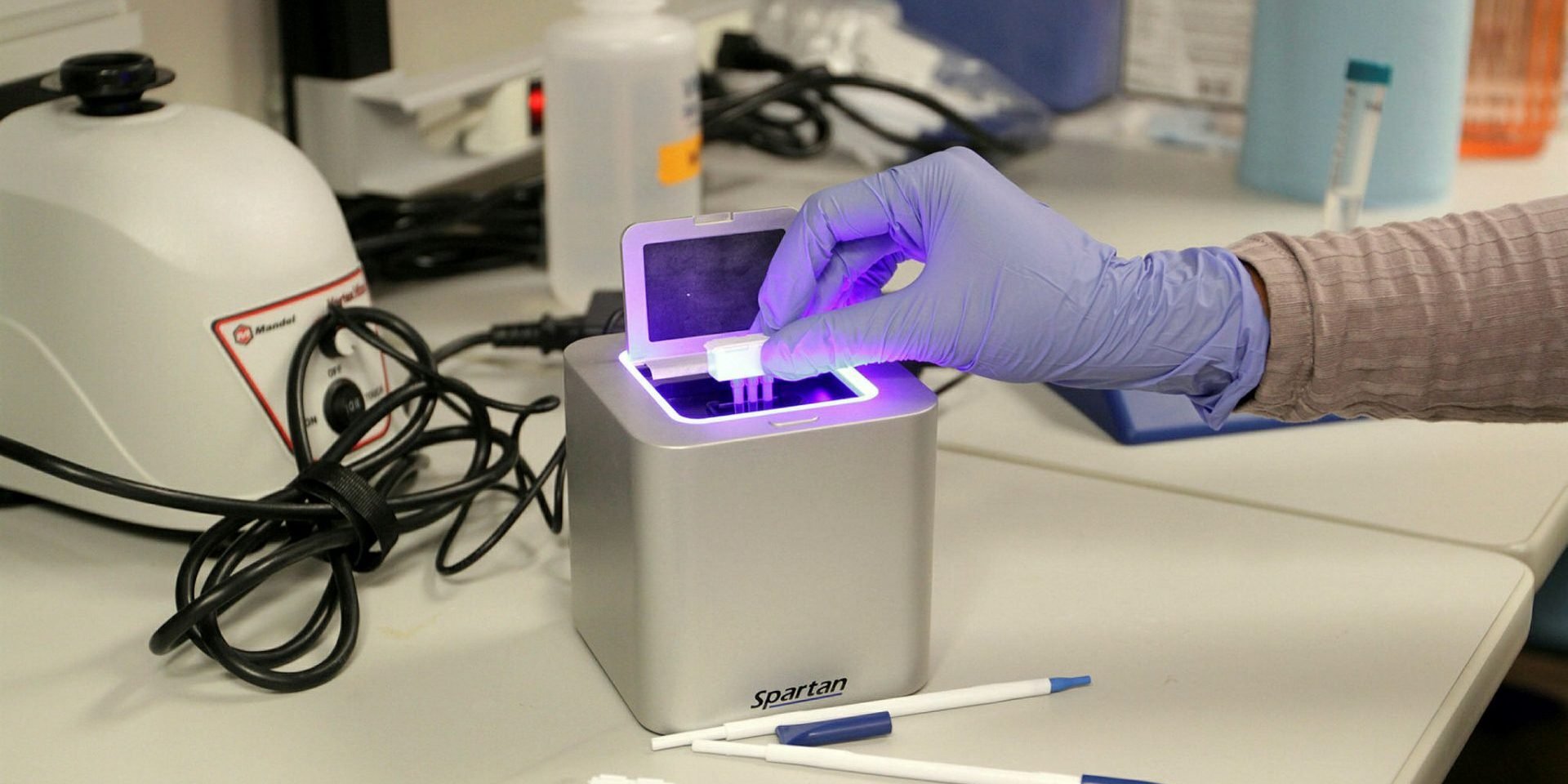

Photograph courtesy of Thao Pham

Instead of making full use of this much-needed supply of talent, we do not recognize or remove the many obstacles in their way. Being an immigrant woman myself, and trained in science, I felt a personal connection to the stories highlighted in a recent report by TechGirls Canada, a non-profit research and advocacy group, that underlined the challenges these women face when they come to Canada.

Like other countries, Canada is facing a critical shortage of workers trained in STEM, one that in the long run will jeopardize our country’s economic growth and competitiveness. Canada also has a large gender disparity gap in this crucial sector, with women accounting for only 23 per cent of the workforce.

Immigrant women are not absent from these fields. The latest census found they numbered 426,000, or 52 per cent of all women in the sector. But despite their international experience and expertise, they have the worst outcomes when it comes to unemployment, under-employment, and the wage gap. They earn on average 55 cents for every dollar earned by non-immigrant men with the same qualifications.

This article was originally published in The Hill Times. Read the full text here.

Thao Pham immigrated to Canada with her family, received her science degrees at McGill University and Université du Québec à Montréal, and held many senior positions in the Government of Canada. She is now Board Chair of the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority, Board Director of Mitacs, and Senior Fellow at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs.

CanadianSME Business Magazine:

Saadia Muzaffar’s Approach to Supporting Immigrant Women

October 2023

“Immigrant women face a very specific set of challenges where they are simultaneously invisible and hypervisible. Despite their world-class experience and expertise, this high-potential and powerful talent pool faces the worst outcomes when it comes to unemployment, underemployment, and wage gap in Canada – yet in the vast majority of spaces where we are encouraging women and girls to choose STEM, we never hear the challenges faced by internationally trained immigrant women who were invited to Canada specifically because of their STEM expertise by our immigration system. In this way, despite their potential, they are invisiblized and not offered the supports that would help them land the jobs where they belong and to get paid equitably for equal work.

On the other hand, an immigrant woman cannot enter a room as just a STEM trained expert – her intersectional identities of being a woman, maybe a racialized woman who has a hijab and an accent and was educated, her immigration status, her international training and experience – also enter the room with her. In that way, these women are hypervisible and held to a higher and often arbitrary set of standards than others in the same labour market, which entrenches their under-employment, unemployment, and the persistent wage gap.

So like many situations women are forced to straddle, STEM-trained immigrant women are put in this impossible situation where there is no way for them to win.”

Read the original article in CanadianSME Business Magazine

The Hill Times:

Greater support needed for invisible majority of Canadian women in STEM

September 2023

“The Royal Canadian Mint has just launched its 2023 commemorative loonie, celebrating 20th century aeronautical engineer Elsie MacGill, a woman who defied the career conventions of her time to become the first woman to design an aircraft. She supervised the production and testing of nearly 1,500 Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft in the Second World War, and was also the first woman elected to the Engineering Institute of Canada. MacGill was a passionate advocate for gender equality in the workplace. Thanks in part to her efforts, women have made extraordinary contributions to science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). But as numerous as these contributions are, they are almost certainly outnumbered by contributions not made, due to women’s historic exclusion from these fields.

We have not yet created the conditions for women to achieve parity in STEM jobs and sectors. Women’s participation in the tech industry, for example, has barely budged over the last two decades, moving from 21 per cent of the workforce to 24 per cent. Most concerningly, after inviting them to Canada for their skills, we are failing immigrant women in STEM more than anyone. Immigration accounts for almost all of Canada’s labour force growth. Our points-based system has built one of the world’s largest internationally trained STEM workforces. Within it, immigrant women make up the majority (52 per cent) of Canada’s women in STEM, a proportion that is increasing every year.

Despite their potential to contribute to advancements that boost productivity and prosperity, they experience worse labour market outcomes compared to immigrant men and non-immigrant women in STEM, with higher unemployment, underemployment, and wage gap rates.

It is an alarming waste of talent. Their skills, education, and job experience are considered to be in high demand. Immigrant women in STEM are aged mostly between 30 to 40, with the majority counting five to 10 years of work experience. Four out of five are fluent in English, and a quarter speak both English and French. Nearly all have a bachelor’s degree in a STEM discipline, with more than half holding a master’s, while just shy of a quarter have a PhD.

With so much going for them, it’s hard to believe that immigrant women in STEM reported an average starting salary in Canada of just $41,000. But it’s true.

This is not a new problem, but now we have numbers—research has only recently revealed the scope and magnitude of the discrepancy in outcomes for immigrant women in STEM. Comparatively few resources are available to design programs and systems to mitigate these entirely preventable barriers.

Employers can and must be part of the solution. Conversations with hiring managers reveal strong enthusiasm—in principle—to hire immigrant women and advance their careers, but in practice this does not consistently translate into results. International credentials and a lack of “Canadian experience” are two quoted barriers that contribute to immigrant unemployment and underemployment. Much is possible to better educate employers on how to accurately evaluate and unlock these workers’ potential.

Government, for its part, should be just as interested in ensuring immigrant women successfully integrate into the labour market as they are in selecting and inviting them to come to Canada. This interest could take the form of increased financial investment for research to understand the full scope of the issue, and for the design and implementation of solutions-focused initiatives for employers that go further than giving one-size-fits-all advice to immigrant women in STEM sectors.

One way employers with an interest in innovation can take action is by moving beyond mentorship. “While a mentor is someone who has knowledge and will share it with you, a sponsor is someone who has power and will use it for you,” wrote Professor Herminia Ibarra of London Business School in the Harvard Business Review. Managers and executives should actively advocate for immigrant women to get a fair chance at valuable project assignments and promotions, and there is an urgent need for evidence-based program design that would enable employers to ensure this is part of their talent retention practices.

In this decade, our next trailblazing woman like Elsie MacGill is probably an immigrant. According to data from Statistics Canada, immigrant STEM graduates are more likely to start a business in Canada than similar graduates who are Canadian by birth. This dynamism is just one reason that Canada invites them here.

Most of us would not call in rocket ship engineers to assign data entry in a call centre, but that is too often the kind of bargain Canada currently offers most immigrant women educated in STEM. We are all worse off for it, but it doesn’t have to be this way. With more research, resources, and solution design, we can ensure Canada’s employers and immigrant women are together on a path to innovation and prosperity.”

Read the original piece in The Hill Times.